Rusholme & Victoria Park Archive

Thomas Wright, 1789 - 1875

“Thomas Wright, the philanthropist of Manchester, distinguished himself as the true friend of forlorn prisoners. He was a man of no position in society. He possessed no wealth, excepting only a rich and loving heart.”

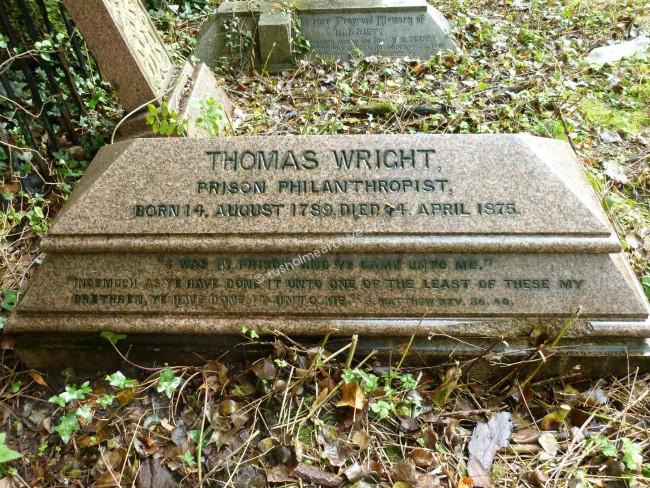

When I referred on a previous page to the graveyard at St James, Birch-in-Rusholme, I did express regret that so many gravestones (with their attendant family history) had been bull-dozed away. However some of the stones that were considered worth saving have been set on the NE side of the graveyard and the one shown in the photograph below is a memorial that is worthy of a page on rusholmearchive.org.

Thomas Wright spent most of his life in Chorlton-on-Medlock, living in Sidney Street. Why he was buried in Rusholme is unclear, but apparently there was a time when St James graveyard was considered a fashionable place of burial. That reason would hardly seem to have applied to Thomas Wright. The following biographical notes are taken from Wikipedia;

“Thomas Wright was a prison philanthropist. He received his education at a Wesleyan Sunday school, and when fifteen years old was apprenticed to an ironfounder, ultimately becoming foreman of the foundry at £3.10s. a week. In 1817, after a few years of indifference to religion, he joined the Congregationalists, and was deacon of the chapel in Grosvenor Street, Piccadilly, Manchester, from 1825 to the end of his life. Among the labourers in the same workshop with him was a discharged convict, whom he saved from dismissal by depositing £20 for the man's good behaviour. This circumstance directed his attention to the reclamation of discharged prisoners, and about 1838 he obtained permission to visit the Salford prison. As he was at work at the foundry from five in the morning until six in the evening, he could spend only his evenings and his Sunday afternoons at the prison, where he became the trusted friend of the inmates, for large numbers of whom on their release he obtained honest employment, his personal guarantee being given in many cases. The value of his labours was made public by the reports of the prison inspectors and chaplains, and he was offered the post of government travelling inspector of prisons at a salary of 800l. This he declined, on the ground that if he were an official his influence would be lessened; but in 1852 he accepted a public testimonial of £3,248., including £100 from the Royal Bounty Fund. With this sum an annuity equal to the amount of his wages was purchased, and he was enabled to give up his situation at the foundry and devote all his time to the ministration of criminals. For some years he attended nearly every unfortunate wretch that was executed in England.

Wright gave evidence before select committees of the House of Commons in 1852 on criminal and destitute juveniles, and in 1854 on public-houses. He was a promoter of the reformatory at Blackley, and worked on behalf of the Boys' Refuge, the Shoeblack Brigade, and the ragged schools of Manchester and Salford. He was strongly in favour of compulsory education.

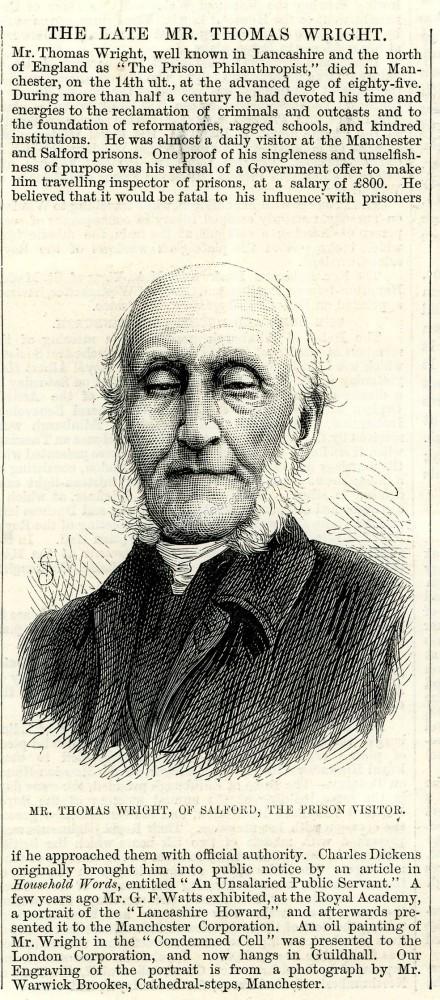

Wright was born at Haddington near Edinburgh, in 1789,[1] his father being a Scotsman and his mother a Manchester woman. Wright died at Manchester on 14 April 1875, and was buried in the churchyard of Birch-in-Rusholme. He was twice married, and had nineteen children.”

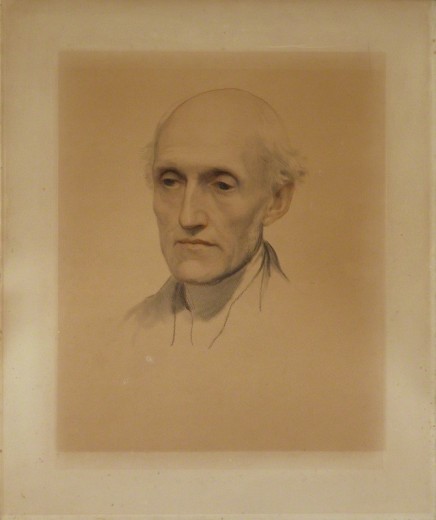

The image above of Thomas Wight is from the National Portrait Gallery and is shown under their Creative Commons copyright Licencing policy; Image licence and download for limited non-commercial, use in non-commercial, amateur projects (e.g. blogs, local societies and family history).

It was in 1852 when he was at the age of 63 that his friends and colleagues in Manchester endeavoured to find Thomas an income that would allow him to devote his time working amongst the poor and particularly the prison population.

One of his friends was Elizabeth Gaskell, (she referred to him as “Our dear Mr Wright”), and she was writing to people all over the country in February 1852 trying to raise support for a pension for Thomas. Charles Dickens was at that time publishing his ‘Household Words’ and on March 6th the following story headed “An unpaid Servant of the State” was printed. As Elizabeth Gaskell regularly wrote for Household Words it may be the case that she was responsible for this item.

You can read the story which is three pages long by downloading the PDF file marked below. This has been taken from the Google free library and is in the public domain.

‘Many thousands attended the funeral’

Thomas Wright was buried on Saturday 17th April 1852. His funeral was reported as follows;

"The remains of the late Mr Thomas Wright., the prison philanthropist, were interred on Saturday in the burial ground connected with Birch Church, Rusholme. Saturday afternoon was fixed for the funeral in order to enable the managers and representatives of the many public institutions with which the deceased had been connected to attend without inconvenience to themselves. The family yielded to a widely expressed desire that the funeral should be public, in the sense that those who desired to follow the remains to the grave should be permitted to do so, and many thousands besides those in the procession assembled in the churchyard to witness the obsequies. The procession was formed in Sidney-street, and started at about three o’clock. It was headed by the band and other inmates of the Industrial Schools, Ardwick Green, and the band from the Barnes Home. About 150 ragged school teachers from Manchester and Salford came next. The Shoeblack Brigade and band from the Boys’ Refuge, Strangeways, were also present together with Mr. Taylor, the treasurer, and Mr. Shaw the secretary; and immediately preceding the hearse were a large number of city missionaries and friends. Following the hearse were three mourning coaches and thirteen private carriages. In the first coach were Mr. K. S. Wright, (the deceased’s son), Miss Wright and Mrs Royle (daughters), and Mr. Howard Wright (grandson). The second coach contained Mr. R. Royle (grandson), Mr. J. Mawson and Mr. W. Craig (nephews), and Mrs Craig; and in the third coach were Mr. T. Wright McDanaid (grandson), Mr. Walter Craig (nephew),, and Mr. and Mrs Schon. Amongst the private carriages were those of Sir J. Iles Mantel, Mr. J. Rylands. Sir J. Watts, Mr. G. Sidebottom, Mr. II. J. Leppoc, Sir J. L Bardsley, Dr. Wilkinson, and Mr. Le Mare. Amongst those either in the procession or the church were Mr. J. Clegg, Captain Leggett (governor of the County Gaol), Mr. A. Megson, Dr. Ledward, Mr H. Hodgson .Mr. Hulton (Clerk to the Visiting Justices of the County Gaol), the Rev. Canon Barnsley, the Rev. W. Caine (late chaplain of the County Gaol), Mr. G. Railton, Mr. E. R. Le-Mare, Mr. It. Johnson, the REV J. Wheeldon, (Late secretary of the Ragged School Union), and Mr. J. Snape, the present secretary. The ragged schools were represented by Mr. A. Forrest and Mr. Wood (Holt Town), Mr. R. B. Taylor (author of the prize essay on ragged schools), Mr. Burtenshaw, Mr Ward and Mr. Passley (Charter Street), Mr A. Allsop (Wood Street), Mr. Leatherbarrow, (Queen Street), Mr. A. Le Mare (Heywood street),Miss Le Mare and Mr. Rollins (Holland- street). The services in the church and at the grave were read by the Revs. W. Doyle and T. A. Stowell. The hymn “For ever with the Lord’’ was sung at the conclusion of the service at the grave. We understand that the family of the deceased have received letters of condolence from Lady Burdett Coutts and the Earl of Shaftesbury. The death of Mr. Wright formed the subject of the sermon at several of the churches in Manchester and Salford yesterday.

The sermon at St. James's, Birch, was preached by Archdeacon Anson, and at the conclusion of the service the Dead March in “Saul” was played."

There was also a brief obituary in the Illustrated London News;

Samuel Smiles was a famous Victorian contemporary of Wright and after his death Smiles devoted a tribute to him in his book, ‘Duty’ published in 1880.

“Thomas Wright, the philanthropist of Manchester, distinguished himself as the true friend of forlorn prisoners. He was a man of no position in society. He possessed no wealth, excepting only a rich and loving heart.”

This tribute from the famous contemporary expressed the admiration of Victorian England for Thomas Wright’s pioneering work in rehabilitating criminals and reintegrating them within normal society - an achievement all the more impressive for being the work of a busy factory foreman without any resources or connections apart from his modest weekly wage (£3.50p) and a reputation for industriousness and honesty.

There are two extracts below from ‘Duty’.

“Employers of labour came to believe in Thomas Wright. They knew him to be a good and benevolent man, and that he would not counsel them wrongly. He took the employers into his confidence, and they usually employed the released felons. Where they had doubts, he guaranteed their fidelity by deposits of his own money—gathered together out of his foreman’s wages of seventy shillings a week.

He went on quietly and unostentatiously in this way— preferring that no notice should be taken of his name, lest it might interfere with the good that he was doing; until he had succeeded in a few years in finding employment for nearly three hundred discharged prisoners! He even succeeded—the worst task of all—in reclaiming women from drunkenness. He would sometimes go miles into the country, to plead with husbands, even on his knees, to take back the wife who was no longer drunken, but was penitent and longing for home”.

“There were many cases in which Mr. Wright could not get employment for the released prisoners. In such cases he either lent them money of his own, or raised a private subscription among his friends, to enable them to emigrate. In this way he assisted 941 discharged prisoners and convicts to go abroad and to begin life under new circumstances and separated from their old companionships. In many cases the discharged prisoners themselves helped him in his philanthropic labours. They got employment for their friends, or they helped to raise subscriptions to enable others to emigrate. Thus charity begot charity.

One of these forlorn emigrants, who had been sent to North America, wrote to Mr. Wright in 1864, addressing him as “My dear adopted father.” He enclosed £2 as a contribution to the London Male Reformatory. The emigrant, who was now a prosperous man, said, “To your never- to-be-forgotten fatherly aid I owe my present success. You were indeed my best, my kindest, and my sole advising friend on this earth. You rescued me from a life of vice by your own unaided help. When all others had turned their faces from me as a miscreant and a vagabond, you, like the prodigal’s father of old, welcomed me back to the paths of virtue and integrity of life, consoling my youthful heart with the hope of brighter days yet in store, and blending your fatherly counsel with a still purer hope beyond the grave. God bless you, dear father! God bless you for all your kindness! Tears of kind remembrances fall from my cheeks as I think upon all your noble efforts for your poor fellow-men.”

The tribute that Samuel Smiles wrote is 9 pages in total. This can be read in PDF format by clicking below.

After his funeral a committee was formed to raise money for a memorial grave stone, "A public meeting being held at the Religious Institute, Corporation Street, to consider the propriety of erecting a monument over the grave".

The Venerable Archdeacon Anson said in reference to Mr. Wright: “I shall be glad to show my real regard for his memory by contributing to a memorial and promoting the work in any way I can. It will, l am sure, be felt that the monument should be in thorough consistency with the simplicity of the character of the good man whom it is to commemorate”.

I can only add that the continuing survival of this memorial gravestone is a wonderful tribute to a highly regarded Manchester citizen from the Victorian era.