Rusholme & Victoria Park Archive

2nd Western General Hospital

Strange friend’ I said, ‘here is no cause to mourn’

‘None’ said the other, ‘save the undone years, the hopelessness’

Words from ‘Strange Meeting’ by Wilfred Owen, MC & war poet, he was a second lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment.

Red Cross nurses made a name for themselves by helping the wounded during the First World War.

After the outbreak of the First World War, the British Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem combined to form the Joint War Committee to pool resources under the protection of the red cross emblem.

Here in Rusholme women were trained in first aid and home nursing, then volunteering on a part-time basis as members of the local voluntary aid detachment, (VAD). In the Red Cross military hospitals in Rusholme the VAD nurses were probably the backbone of nursing. This young woman above was photographed by Frank Wyles at his Birch Studio, 124 Dickenson Road, Rusholme.

When WW1 started in 1914 the 2nd Western General Hospital was established in Manchester where its HQ was Central High School for Boys, Whitworth Street, the photograph below is undated.

Initially 520 beds were provided at this site but during the duration of the war a total of 25,000 beds came under the one command. This huge number of hospital beds were scattered throughout Manchester and surrounding towns, becoming the largest military hospital in the UK. It is hard to imagine in the absence of a National Health Service how so many injured service-men could be effectively managed.

In 1924 Sherratt & Hughes published 'A Short History of Manchester and Salford'. Written by F A Bruton chapter 31 recalls the role that Manchester played in WW1. The events must have been very fresh in the authors mind and the following few sentences from this chapter give some idea of the role that Manchester played in caring for the wounded service-men.

"Meanwhile the War Office looked to Manchester to render important aid in the treatment of the wounded, who were now pouring back across the Channel. War had only just been declared when the principal new school buildings in Manchester and Salford were commandeered as military hospitals, and an enormous effort was made besides by the Red Cross Societies and by private individuals unofficially, to meet the demand, not only for hospital treatment, but also for Rest Homes for the convalescents. Trains were met at all hours of the night by committees of ladies, who provided refreshments, and assisted in removing the wounded; clubs were started, the grounds of beautiful country-houses were thrown open to the men in blue hospital dress; the gates of hundreds of villa residences bore the notice : “Wounded soldiers may rest in this garden”; motor rides were organised as long as petrol could be obtained; innumerable concerts and entertainments were arranged, theatres and palaces gave free matinees; and a special committee was formed to provide a constant supply of the necessary hospital garments and other details. Once, when the War Office issued an appeal for cotton-wool respirators as a protection against poison-gas, the girls in the high schools worked with such expedition that the supply almost immediately overstepped the demand.

Hand in hand with the British Red Cross Society worked such organizations as the St. John’s Ambulance Association, the Wounded Soldiers’ Tobacco Fund, the Music in War-time Committee, the Lloyd’s Bank Entertainment Fund, and the Nurses’ Rest Room. During the War Manchester and Salford constituted perhaps the largest hospital centre in the United Kingdom. Over a thousand ambulance trains arrived, conveying nearly 180,000 cases. Throughout, the conveyance of the wounded was carried on by voluntary work, about 180 cars and ambulances being employed. The total number of cases transferred was over 700,000. The total hospital accommodation in Manchester and Salford was 10,790. The Red Cross hospitals alone dealt with 34,762 cases, and the approximate cost of maintenance of these institutions was, £257,000. The members of Voluntary Aid Detachments numbered 3,575. The working parties, besides providing for all local requirements, despatched close upon 400,000 articles to the front; in addition to this, the War Hospital Supply Rooms, centred at Dover House in Oxford Road, and differentiated as Bandage Room, Garment Room, Linen Room, and Slipper Room, supplied very nearly 200,000. For the work at Dover House alone a sum of nearly £6,000 was raised.

There was a special department for making enquiries about wounded and missing men; over 8,000 reports were actually received in answer to nearly 13,000 enquiries. If the relatives of the sick and wounded came to Manchester, they found a special Hostel provided for them. Twenty Ambulance Air Raid stations were maintained.

Lastly, the organisation of permanent help for the disabled men of East Lancashire was largely centred in Manchester and Salford. A sum of £100,000 was raised for Homes for disabled soldiers and sailors; a further sum of £20,000 was subscribed for the treatment of cases at the orthopaedic hospital. There was also a special hospital provided for limbless cases. Surely we may add here that one thing that will always be remembered by those who were privileged to assist in any of these ways, is the unfailing cheerfulness, buoyancy, good humour, and unaffected modesty, of these wounded men, many of whom, after all, maimed, mutilated, and disabled, some in the bloom of youth, some in the prime of life, brought long tedious journeys on stretchers, across a stormy channel, over hundreds of miles of railway, with years of pain and slow recovery before them, with prospects blighted - have been and will be the greatest sufferers. These things, however, of which we have but too frequent reminders in our streets every day, only serve to bring home the realities that are inseparable from war. Nor must we forget how familiar, and how frequently upon our lips in those days, was the fatal word “ Killed,” and how much it meant to those more immediately concerned."

Prior to the 1st World War the greatest number of casualties returned to Britain, 21,157 were from fighting in South Africa during 1899-1902. In 1916 523,153 casualties had been returned to Great Britain from the slaughter on the Somme.

There had been a review of the Army Medical services in 1907 and from that a voluntary service, the British Red Cross and St Johns Ambulance constituted a Home Hospital Reserve, whilst the members of the Royal Army Medical Corps went overseas to work in the front line.

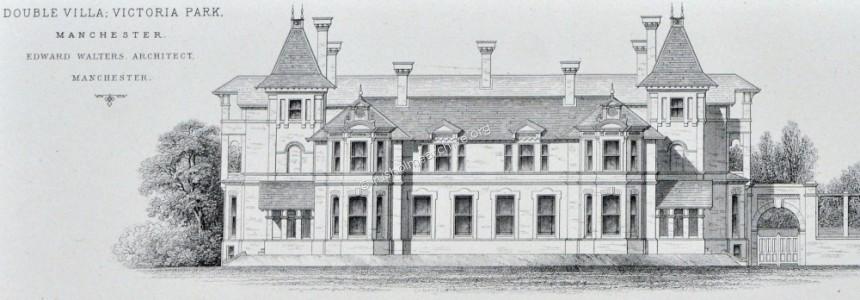

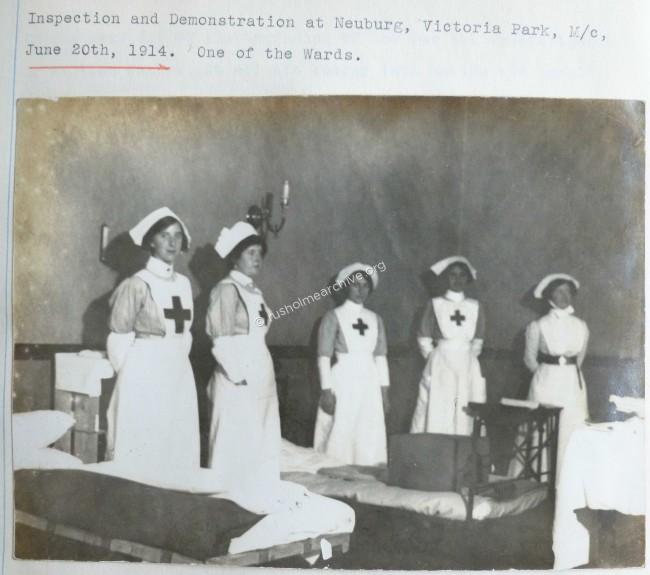

In Rusholme, Heald Place School was so new that only having just been constructed it was taken over as a hospital before pupils had even been admitted; in Victoria Park the Rusholme Red Cross opened Neuberg, one of the large houses on Daisy Bank Road. This was classified as one of the auxiliary hospitals initially providing some 40 beds. Later in 1916 the Red Cross purchased Grangethorpe, the large mansion on the southern edge of Platt Fields where six wards, an operating block, gymnasium, nurse’s accommodation and rehabilitation workshops were built in the gardens.

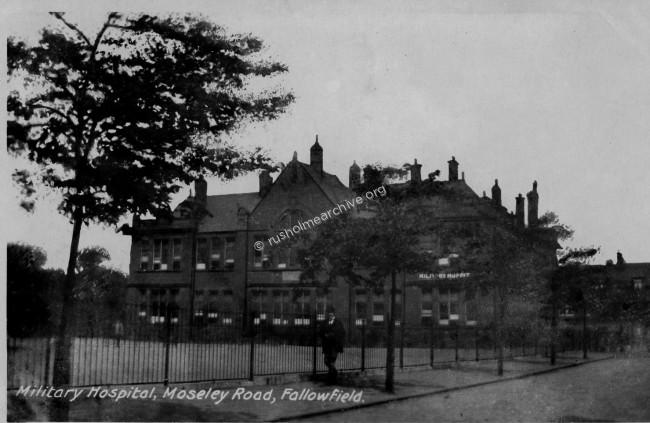

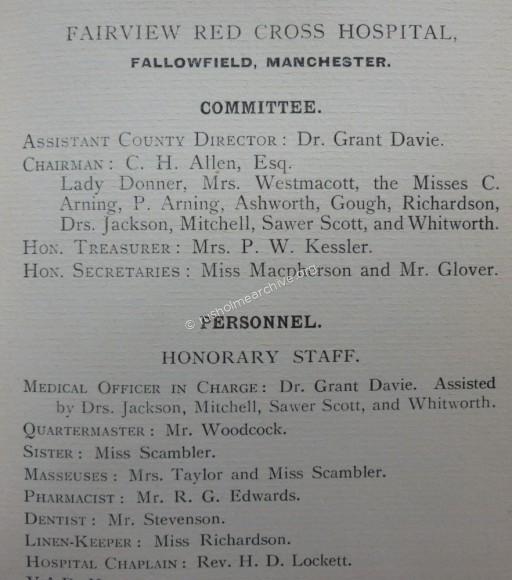

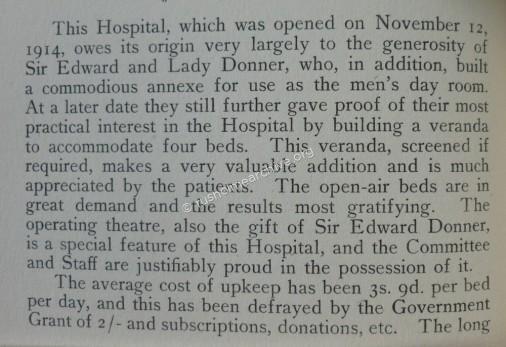

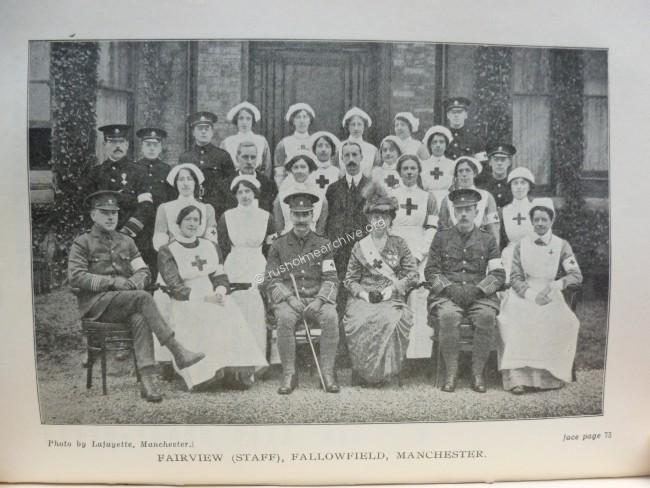

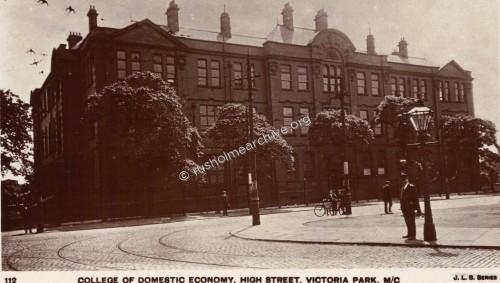

In the area immediately around Rusholme, the government requisitioned Ducie Avenue School on the north side of Whitworth Park, the Elizabeth Gaskell School of Domestic Economy on High Street,(Hathersage Rd) and the Moseley Road school in Fallowfield. Nearby over 1200 beds were under canvas in the grounds of The Firs, the mansion built by Sir Joseph Whitworth off of Oak Drive, Fallowfield. Fairview, another large house on Wilbraham Road in Fallowfield was acquired by the Red Cross and used as a hospital with initially 20 beds although eventually 36 beds were provided.

Below photograph dated 1917 of the Moseley Road School in use as a Military Hospital for 'Other Ranks', i.e. not officers. There were 155 beds provided here.

Below is a small piece of woven tape - to be worn on a lapel?

A letter to the Guardian in November 1914 illustrates the voluntary nature of these Red Cross auxiliary hospitals. Lady Donner of Oak Drive in Fallowfield was a member of the Fallowfield Red Cross branch and her letter appealed for any suitable materials for the Fairview hospital, viz;

'As we earnestly desire the hospital to be suitably equipped and adequately maintained, we appeal to the charitable public for donations of money, and especially the following articles:—

1. Surgical dressings, including lint, cotton wool, gauze, jaeconet, and bandages.

2. Enamelled ware - suitable for dressing and nursing- purposes.

3. Bed-rests, rubber water-bottles, wheel chairs. Bath-chair.

4. An operating-table.

5. Hospital suits, bedroom slippers, and pocket-handkerchiefs.

6. Brushes and combs, sponges, nail brushes tooth brushes, tooth paste or powder, and soap.

7. Tobacco, pipes, cigarettes, newspapers, illustrated magazines, chocolate, fruit, etc.

8. All foodstuffs.

Cheques and money will be gratefully acknowledged by the hon. treasurer, Fern Lea Wilmslow Road. Fallowfield, and any of the above articles will be received by Quartermaster Renshaw at the hospital.’

The following three items about Fairfield Hospital are taken from a review of the work done by the East Lancs Red Cross during the first year of the war. The book was published by Sherratt & Hughes, Manchester booksellers, in 1916 and refers to all of the Red Cross hospitals in East Lancs. It is a valuable source of information for this page about Rusholme Military Hospitals.

The following three items about Fairfield Hospital are taken from a review of the work done by the East Lancs Red Cross during the first year of the war. The book was published by Sherratt & Hughes, Manchester booksellers, in 1916 and refers to all of the Red Cross hospitals in East Lancs. It is a valuable source of information for this page about Rusholme Military Hospitals.

The photograph below is from the Fallowfield photographic studio of H Clow Boag, The young man is presumably a patient, (perhaps from Fairview?), as he is wearing his 'hospital blue' unifom

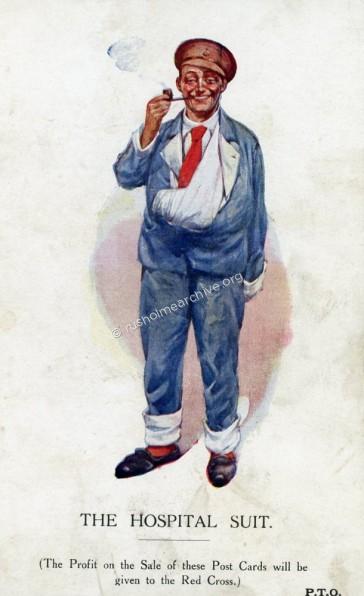

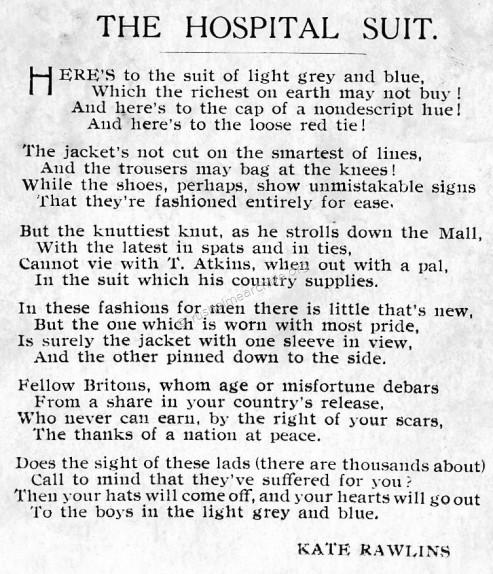

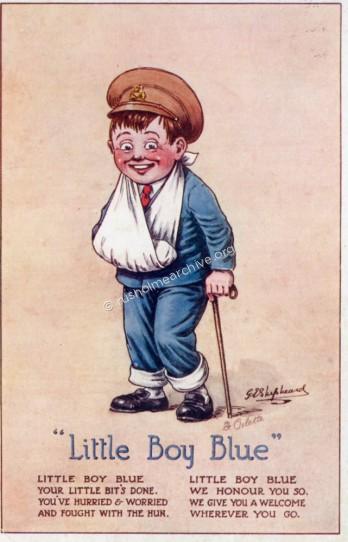

With the arrival of the 1914 - 1918 First World War the postcard industry turned its attention to patriotic illustration. Postcard publishers and artists did their utmost to support their country's war effort.

WW1 Postcard above by Donald McGill, famous for his 'saucy' sea-side postcards he created an enormous output of cards during the war - the following is a note from Wikipeadia:

'During the First World War he produced anti German propaganda in the form of humorous post cards. His cards from this time period reflected on the war both from the opinion, as he saw it, of the men serving, as well as the realities facing the families remaining home. Cards dealing with the so-called "home front" covered issues such as war-time rationing, home service, war profiteers, spy scares, interned aliens, among other issues. Recruitment and "slackers" were other topics covered. Many cards were designed to appeal to the soldier who wished to send a card home to his sweetheart and these cards showed couples. Cards showed soldiers in training, and there were many lighthearted jokes about the Scottish soldier and his kilt. A few cards showed images of Nursing Sisters, and at least one showed three female Munition workers. Of all these cards, there were relatively few depicting a soldier in action. A number of the cards depicted men in the Navy. Of all the military themed post cards, only a few of these were serious – such as one showing a British Red Cross Medic caring for a wounded German soldier.'

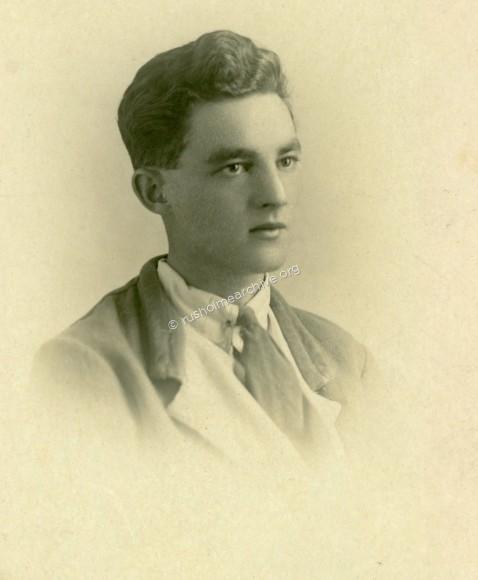

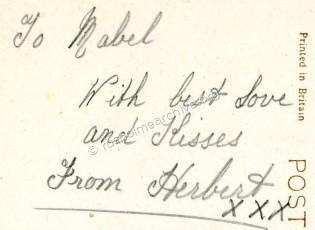

The postcard below must have been popular amongst service men to send their sweethearts - I have also shown the message on the reverse, did Herbert ever return home to Mabel?

Lord Kitchener, perhaps the most iconic WW1 Military figure shown here on the postcard below on the Manchester Town Hall steps with the Lord Mayor of Manchester and other Military and Civic dignitaries. The occasion was the March Past of Manchester Battalions on March 21st 1915.

(Not a Rusholme postcard but does illustrate the patriotic fervour of the period).

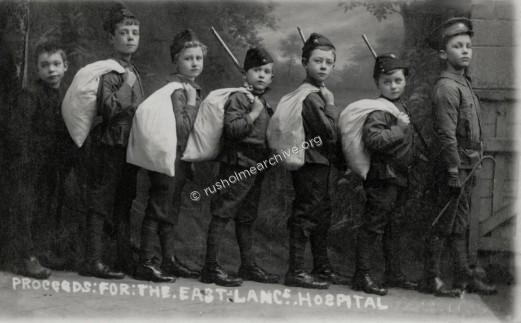

Two photographic postcards below show children presumably helping in the war effort. The first is of girls photographed in nursing(?) uniforms, I think the girls were pupils at Longsight Grammar School, Daisy Bank Road, Victoria Park. It was probably taken in 1916 and appears to be in the garden of Frank Wyles 'Birch Studio' at 124 Dickenson Road, Rusholme. The second photograph of the young boys in soldiers uniforms is postmarked Accrington and has a message on the back; 'These are my little helpers'.

Below is a photograph of the exterior (and underneath a close-up) of the Ducie Avenue boys school.

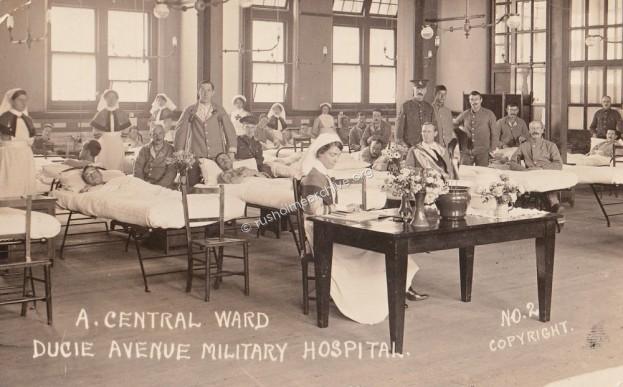

Interior views of a ward, below.

At the Ducie Avenue hospital an orthopaedic section was established with a young RAMC Captain Harry Platt in charge assisted by Professor Stopford. When the Grangethorpe Hospital was opened in 1917 all of the orthopaedic work was transferred here and it became a very important centre for the reconstruction of soldiers damaged limbs.

3 Photographs below Ducie Avenue hospital patients & nurses dated 1916

The postcard below is undated, but it must have popular with soldiers recovering from their wounds.

However there is an interesting story that has been sent to me by Peter Harrington who now lives in America. Peter and his family had lived in Manchester and he briefly told me how his grandmother had met her future husband at Ducie Hospital, see the note below the postcard.

“My grandmother, Beatrice Godfrey, served as a VAD nurse at Ducie Avenue Military Hospital from 1915 until 1919. She met her husband, James Whitehurst, Manchester Regiment, who was there as a critically wounded soldier. She also served at Grangethorpe where Professor Sir Harry Platt performed innovative orthopaedic work on my grandfather. I am attaching photographs of my grandmother, Beatrice Godfrey in her nurse's uniform standing next to her brother, Edward George Godfrey (killed April 1918); a small portrait of my grandmother; and a picture of my grandfather, James Whitehurst sitting next to the man who supposedly saved him by crawling out of the trench and pulling him back to safety. Also, a photograph taken at Grangethorpe (I believe), with my grandfather seated at the table, second from left.”

Click on any photograph in the gallery below to see the full picture.

Grangethorpe Military Hospital

In the early 1880’s a large mansion, set in 11 acres, was built on the southerly edge of the Platt Hall estate. Grangethorpe, illustrated below, was built for the Moseley family, Manchester industrialists who were involved in the manufacture of rubber products. After the Moseley family left Grangethorpe it eventually became the home (before the outbreak of WW1) of Herbert Smith-Carrington, a director of the Whitworth-Armstrong engineering company.

His death in March 1917 was just after he sold the property to the Red Cross who intended to use the mansion as a home where badly injured service-men could be offered long-term nursing care.

However the Ministry of War was in need of an orthopaedic hospital in the Manchester area; the facility at the Ducie Avenue School hospital premises nearby in Whitworth Park being inadequate.

The War Office prevailed upon the Red Cross to use the grounds to build and fully equip six wards, an operating theatre, a gymnasium and an administrative block. Accommodation for the nursing staff was also built within the grounds whilst the Matron & other senior medical staff were housed in Grangethorpe. The service officers who were patients also stayed in the mansion whilst other ranks were accommodated in the six wards. Grangethorpe then became a military hospital and although the Red Cross owned Grangethorpe, it let the premises rent & rate-free to the War Office and continued to help by supplying auxiliary nursing staff.

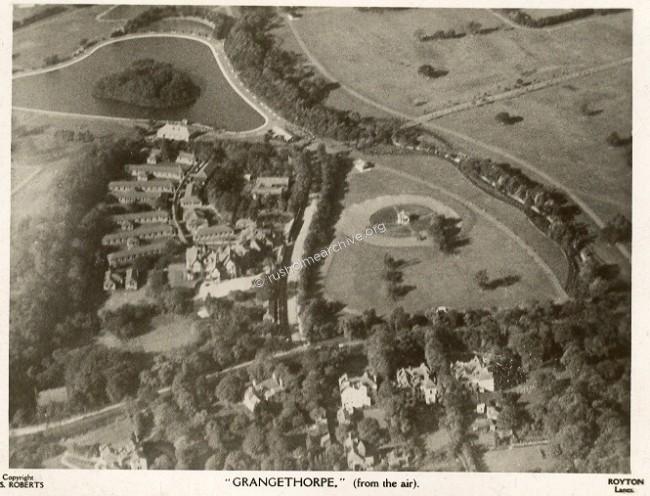

In the aerial photograph below of Grangethorpe the lake in Platt Fields is clearly seen in the top left, the bandstand is away to the right and in the foreground the large mansions are facing onto Wilmslow Road. The wards and other accommodation can be seen in the grounds of Grangethorpe which is the gabled building centre left.

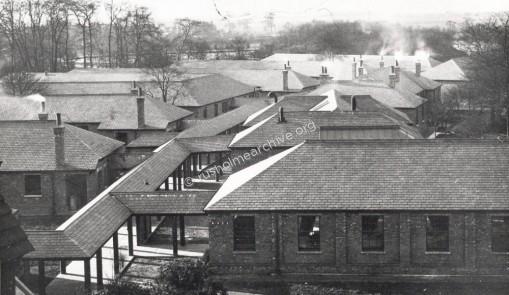

In the view below you can see the wards connected by a covered walkway - presumably the view was taken from an upstairs room inside the Grangethorpe mansion. (MHSGA)

In November 1917 the hospital opened and the orthopaedic department at Ducie Avenue School relocated to Grangethorpe. The hospital remained under the Ministry of War until August 1919 when the Ministry of Pensions took over the hospital until 1929.

The work that was done at Ducie Avenue continued at Grangethorpe, and with a distinguished team of specialists, Grangethorpe Hospital acquired a reputation for pioneer work on the reconstruction of damaged limb nerves, tendon transplants and bone grafts. Amongst the staff were surgeons who were to achieve notable success in their careers, but it was Professor Sir Harry Platt, who had the longest association with Grangethorpe; first as Captain Platt, R.A.M.C. (T.F.) attached to the '2nd. Western' in charge of the Military orthopaedic section, & later, as Senior Surgeon, Ministry of Pensions Hospital until Grangethorpe closed.

Two views below of patients in the wards at Grangethorpe. (MHSGA)

Nursing staff with the superintendent in the photograph below - not dated (MHSGA)

Another member of the clinical staff was Sergeant Jasper Redfern. He had joined the RAMC in 1914 with a particular interest in what was then the pioneering work of using roentgen rays. The small x-ray department undertook valuable work, but at considerable personal cost to the radiographers, Jasper Redfern gradually losing all of his fingers because of radiation exposure. He finally died of cancer in 1929, the cause of his death also being attributed to the excess exposure to x-rays.

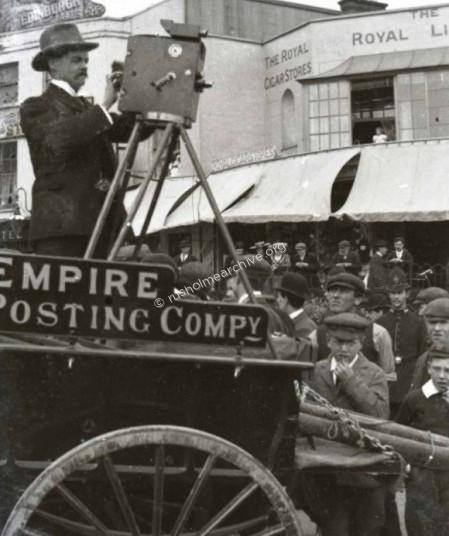

Prior to joining the Army Medical Corps Jasper Redfern had been very much involved in cinematographic work in the north of England. Nowadays he is regarded as one of the pioneers of Cinematography in the late Victorian/early Edwardian period. In the 1911 Census he was living in Salford and he describes his occupation;

Musical Hall Proprietor And Cinematograph Expert And Manufacturer And Producer Of Films And Apparatus + Qualified Optologist + Optician.

The photograph below is clealy relating to his work as a Cinematographer; this is in in The Fred Holmes Collection of The National Fairground Archive at Sheffield University. The photograph is copyright of Professor Roger Waterhouse and I should like to thank him for giving permission to display the image. The restoration work on the photograph has been done by Dr John Bradley.

Photograph below is dated 1918 - captioned "Our Sports" Day, Grangethorpe Lawn - June 1918.

The reputation of the Hospital grew and in March 1920 H.M. King George V visited Grangethorpe Hospital. In 1921 came a second royal visit by the Prince of Wales. He is seen in the photograph below. (MHSGA)

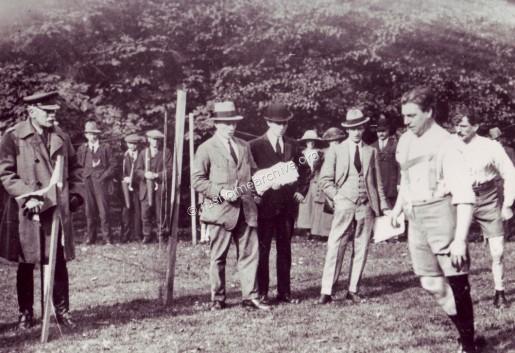

In 1922 the Manchester Guardian referred to a visit to Grangethorpe by General Haig who had come to see patients playing sports games. He can be seen in the two photographs below. (MHSGA)

The Guardian particularly mentioned the success of the men in overcoming their injuries;

“At Grangethorpe you will find men who have brought the use of artificial limbs to so sensitive a pitch that with the touch of a wooden foot they will recognise such things as a small ball of paper, a pebble, a pencil, a cigarette. You will find there men who walk so upright and alert that it would be a keen observer who recognised a wooden leg; men who run, jump over a succcession of gradually raised obstacles and kick footballs. There are cases enough to prove that no one who is prepared to put time and will power into certain simple exercises need be hampered overmuch by the loss of a limb”.

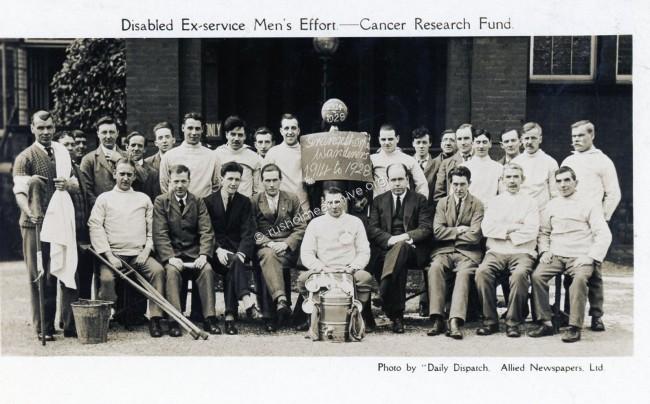

Grangethorpe Wanderers was the name used by the hospital football team; the photograph below must have been taken not long before the hospital closed.

Private John A Harwood.

I came across this story when researching information about Grangethorpe hospital; it was published on www.cottontown.org, a community website about Blackburn & Darwen. Written by Harold Heys, he tells the story of his grandfather, Private Harwood who was grievously injured during WW1. It does not reflect in any way on the treatment and care provided at Grangethorpe Hospital, but as Private Harwood had died at Grangethorpe in very sad circumstances I thought it well worth you having the opportunity to read this story. I should like to take this opportunity of thanking Harold Heys for giving rusholmearchive.org permission to reproduce the story.

HARD AS NAILS by Harold Heys.

HARD AS NAILS by Harold Heys.

“SURGERY - not many years ago - was often rough and ready, especially in and around the battlefields. In the early years of the last century standards were sometimes poor, even in hospitals. This photograph is of an X-ray on the left leg of soldier John Albert Harwood of Darwen who was shot while serving in the 1914-18 war. And, yes, those are rusting joiner's nails pinning the bones together...

John Albert enlisted in the East Lancashire Regiment and later transferred to the 1st Manchester Regiment. A ship he was on was machine-gunned and he was hit in the left knee.

Back in England a Canadian surgeon named Joyce carried out an experimental operation at a military hospital near Reading, cutting away shattered bone from above and below the knee and fitting the bones together with ordinary nails - a six inch round-headed nail and a four inch countersunk nail. Private Harwood had nearly 200 stitches in the leg and was in hospital for 18 months.

A professional strong man before the war, Mr Harwood set up as a shoe maker and clog repairer in Pitt Street, Darwen, and he and his wife Bertha had a fourth child. However, as the nails rusted away, blood poisoning set in.

John Albert Harwood was a brave and a hard man, but he was in agony in his final months and he died in Grangethorpe Military Hospital, Manchester, in April 1924.

Consultant surgeon Hugh Thomas, one of the foremost authorities on war wounds, examined the X-ray photograph a few years ago and described the attempted fusion as "extremely crude." His "uncomfortable conclusion" was that it would have caused "very considerable pain, suffering and continued infection."

Mr Thomas said he had attempted to discover whether the use of nails in this manner had ever been a feature in our military hospitals "but everyone was reluctant to admit this - very understandably." He said he had never come across a case quite like it.

It's perhaps not surprising that Authority, over the years, has chosen to turn something of a blind eye to the sad story of the experimental operation on Private Harwood's leg. It isn't the sort of image the Army is keen to promote, even now. The Imperial War Museum North in Trafford were very enthusiastic a few years ago but then, suddenly, they lost interest.

Private Harwood left his widow to bring up four children; two boys, Tom, aged 13 and Joe, aged 11 and two girls, Margaret, aged 7 and a baby, Mabel. He was 38 years old.

In his 90s, Tom remembers his father coming home for the first time in his hospital "blues". "On his left leg he wore a boot which was built up several inches and he had to use crutches to get about. We were in very poor circumstances. We didn't have any carpets or lino on the floor, just sand. We used to buy it in a loaf tin for a penny.

"Before he became really bad he managed to get my mother pregnant again. We didn't know, but one day we were sent to a neighbour's house and when we came back we found we had another member of the family.

"My father became seriously ill and he used to have kidney fits and thrash around on the bed. My mother used to run next door for help and two big lads called Hindle would come and sit on him to hold him down because he was so strong.

"We couldn't afford to go and see him when he was finally taken to hospital because his fits had become so bad. We phoned or telegraphed occasionally from the post office and one day I remember watching as the chap on the counter wrote out a note that my father had died that morning. I had to go and tell my mum."

Tom remembers the funeral well. "It was quite a modern affair because instead of the usual horsedrawn hearse we had a motorcar. I remember all the men at the side of the road doffing their caps as we passed. It was a traditional courtesy in those days”.

John Albert Harwood died of nephritis - inflammation of the kidneys - and uraemia, a serious toxic condition caused by an accumulation in the blood of waste products. It is characterised by violent headaches, vomiting and, in its acute form, convulsions and coma.

His widow lived to be 90 and is buried in the same grave at Darwen Cemetery.”

Grangethorpe Hospital was finally closed by the Ministry of Pensions in October 1929; by then there were only 38 patients and these were transferred to hospitals in Liverpool & Leeds.

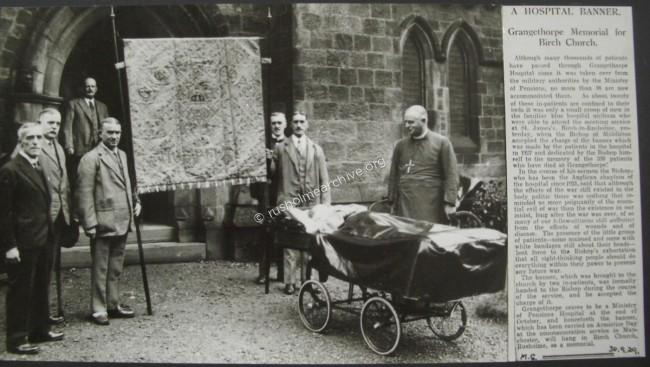

It is worth remembering that 15,000 patients were treated during the 12 years that Grangethorpe was open, sadly 330 of these men died and a book of remembrance, listing their names was placed in the care of St James Church, Birch-in-Rusholme.

Closure Service at St James, Birch-in-Rusholme.

In the report & photograph below, published by the Manchester Guardian on 30th September 1929, some of the remaining patients presented to the Bishop of Middleton the hand-worked banner that they are seen holding. This banner had been made by men at Grangethorpe with help from the Manchester School of Needlework. Together with the Book of Remembrance referred to in the previous paragraph the banner was left at St James in memory of the service-men from Grangethorpe who had regularly worshipped at St James while they were at the hospital. The Bishop of Middleton, the Rev Parsons had served as the Anglican chaplain to Grangethorpe since 1921.

The photograph & the accompanying article, (M315/1/42/3), are reproduced by courtesy of the Greater Manchester County Records Office.

After the Ministry of Pensions closed Grangethorpe the Red Cross handed the hospital over to the Manchester Royal Infirmary. Initially there were plans to create a specialist orthopaedic dept for the MRI but this plan did not proceed and the possibility of it being used as a mental institution was also considered. Meanwhile the workshops that had been created for the military patients were used for training disabled adolescents between 130 and 1936.

As the premises had generally stayed empty during this period it seems that the Royal Infirmary Governors were relieved by an offer from the Manchester High School for Girls of £11,000 to buy Grangethorpe.

This would enable the Girls High School to move from its overcrowded premises in Dover Street, (near Manchester University) and build a larger, modern school. Raising the necessary finance took some time and it was not until 1939 that the new school opened.

Some new schoolrooms had been built but early in 1940 a German landmine was dropped over the site and most of the buildings, both old & new were destroyed – fortunately without any loss of life. It was not until the war was over that rebuilding started and finally in 1951 that the school was opened where it remains to the present date.

The gallery of photographs below show the scale of damage to the newly built school, click on any image and the photo will expand. (MHSGA)

I am particularly grateful for the help given by the Archivist at Manchester High School for Girls, Dr Christine Joy who has kindly provided photographs from the School Archive. These photographs are marked in brackets (MHSGA).

If you would like to view the Archive at Manchester High School for Girls follow the link below.

I understand that the school is planning to erect a memorial commemorating the role of Grangethorpe Military Hospital during WW1

In the photograph below, facing onto High Street, (Hathersage Road) is the Elizabeth Gaskell School of Domestic Economy, undated so I am not able to identify whether or not it was occupied at this time by the 2nd Western Hospital. I understand that this hospital provided a 170 beds exclusively for Officers.

The three photographs below, (kindly donated by Bob Potts), are of the nursing staff at High Stret Military Hospital. On the back of one, dated Jan 1917, the writes to tell her sister that she is just coming off a day shift at 2.30 pm and later that day at 7.30 pm has to start a week of night duty.

The photograph below is of Lydia Kayasht, (centre), a famous Russian dancer. It was taken at the Elizabeth Gaskell School of Domestic Economy in September 1915 when the premises were being used as a hospital during WW1.

The visit of Lydia to the hospital (seen below with convalescing soldiers on her arms), was reported on September 25th in the Manchester Evening News;

'Famous Russian dancer at Military Hospital: Miss Lydia Kyasht accompanied by George Reynolds manager of Manchester Hippodrome visited the High Street Hospital, and presented the soldiers, among whom were a number of New Zealanders who had just arrived from the Dardenelles, with gifts from the Russian people'.

Lydia Kyasht (25 March 1885 — 11 January 1959) was a Russian-British ballerina and dance teacher. She was described by one critic as "the World's Most Beautiful Dancer" in 1914.

Below is a page from 'The Tatler' magazine. Published October 13th 1915, it is a national report report of the visit by Lydia to the wounded soldiers in Rusholme.

Signed photo below of Lydia, "The Worlds Most Beautiful Dancer"

Neuberg, (later known as Newbury) on Daisy Bank Road in the photograph below

Newbury apparently started its life, (like so many other properties in Victoria Park), as a home built for a German textile merchant but it has had a close history allied to the medical profession.

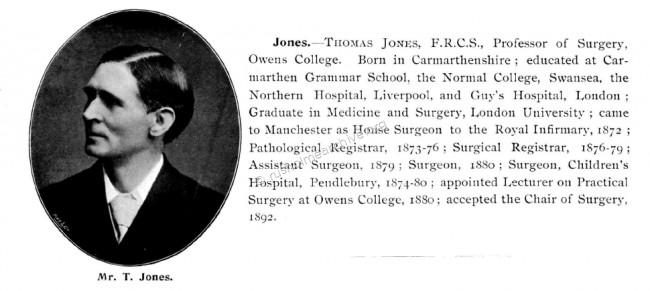

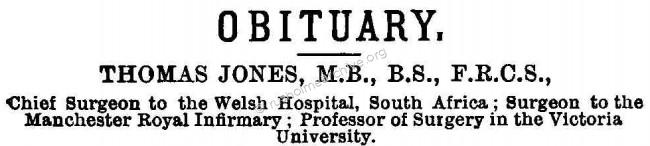

In the late 19th century it became the home of Professor Thomas Jones.

A Welsh hospital was established in South Africa during the Boer War and Thomas Jones left his family and home in Victoria Park to become the surgeon-in-charge. Sadly very soon after he arrived he contracted enteric fever, (typhoid) and died at the comparatively young age of 49, June 18th 1900.

The death of Professor Thomas Jones, of Manchester, Chief Surgeon of the Welsh Army Hospital, which occurred at Springfontein, in the Orange River Colony, on June 18th, is an event which has caused widespread and profound sorrow. The profession has lost an eminent surgeon in the prime of his life, for he was only 49 years of age. He was generally acknowledged to be an excellent practical teacher, a careful and sound diagnostician, and a bold, skilful, and dexterous operator.

The 3 photographs below are of patients at Newbury hospital, the first is undated whilst the next two are 1916 & 1917 respectively.

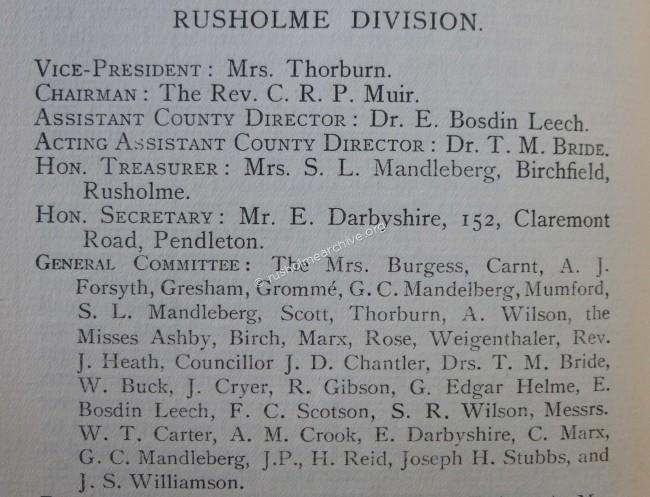

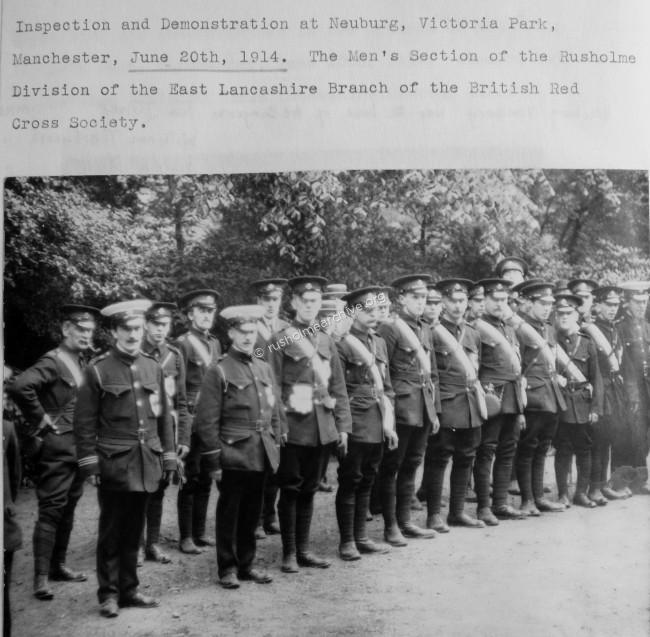

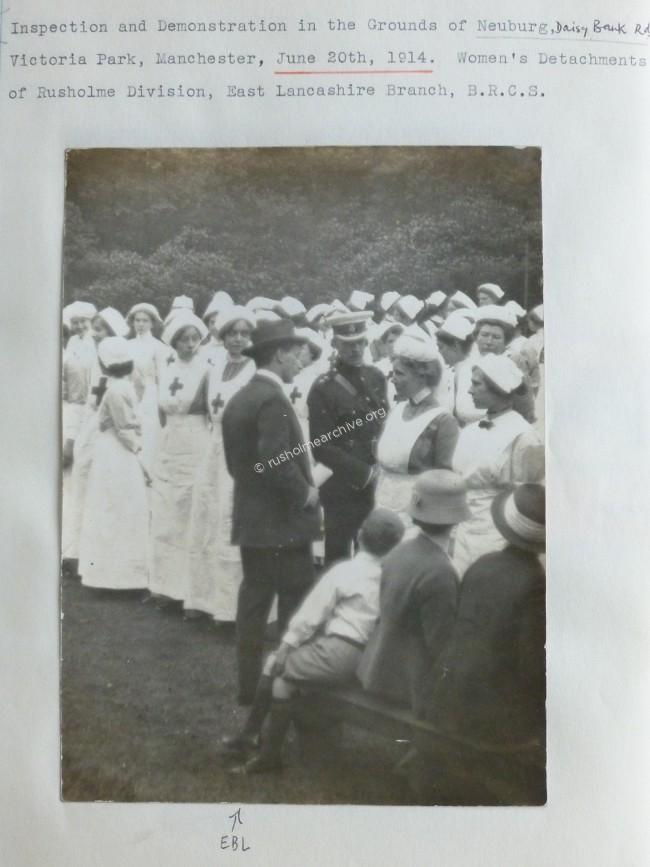

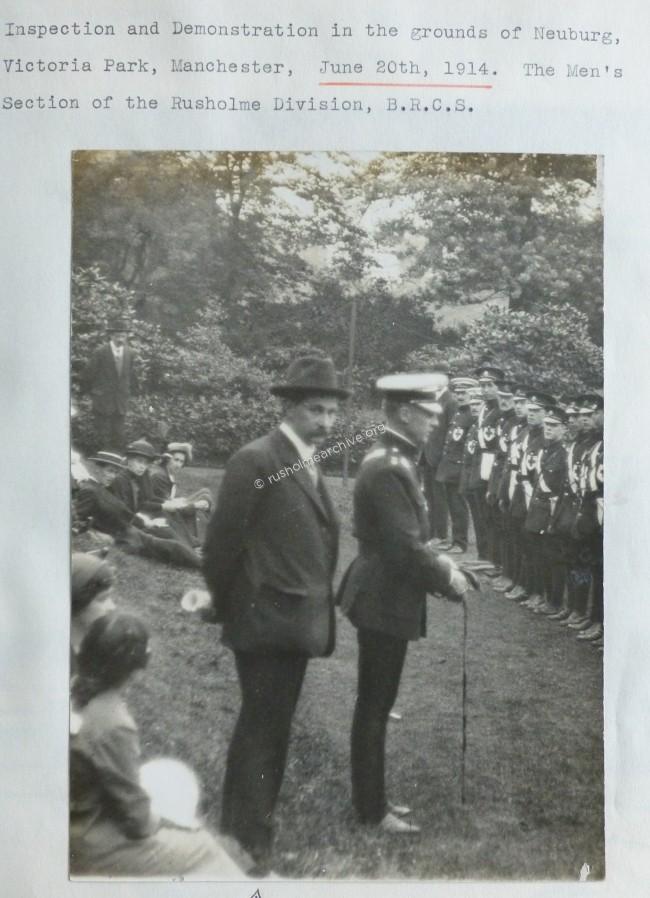

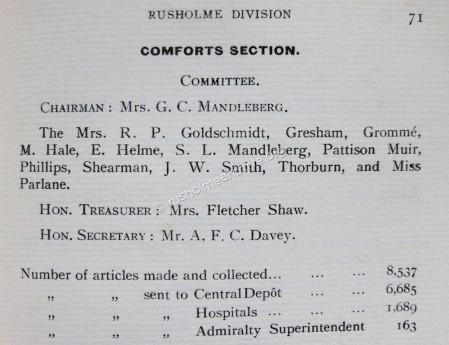

In March 1911 the Rusholme division of the Red Cross was formed after a public meeting that was held at the Manchester Royal Infirmary. The Rusholme Division also included the areas of Victoria Park, Chorlton-on-Medlock and Greenheys.

It is worth remembering that at this time the struggle for women’s suffrage was considered by many to be both violent and controversial. Amongst those present at the meeting called to encourage volunteers for the Rusholme Red Cross was Sir William Grantham, a former Tory politician and controversial judge. He made the following comments to the assembly;

"That in commending the scheme, women should try to do something for the State as well as their brothers. Until they reached women suffrage and women joined the ranks of the army — he did not know if that was what they intended to do when they got the suffrage — they would have to depend upon men to fight the battles; but the women might do something to relieve them, and to help them when they were suffering from sickness or wounds. The women of England should be the first to come forward. A good many people, if they were asked what they were doing for their country, would have to say that they were not doing much. There was no better way of doing something than to help such a movement. Anything that assisted the soldiers more than doubled the ranks of the army. It was not only the men who were killed in war who were lost to an army. More than twice that number were lost to sickness”

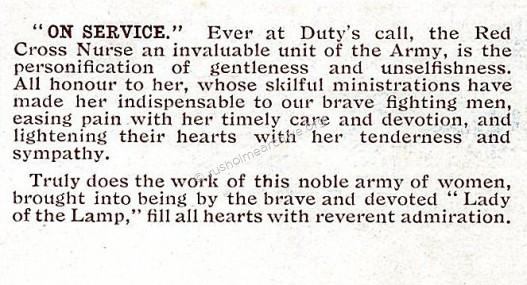

Text below is from the back of the above postcard.

Red Cross nurses made a name for themselves by helping the wounded during the First World War.

After the outbreak of the First World War, the British Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem combined to form the Joint War Committee to pool resources under the protection of the red cross emblem. Because the British Red Cross had secured buildings, equipment and staff, the organisation was able to set up temporary hospitals as soon as wounded men began to arrive from abroad.

The buildings varied widely, ranging from town halls and schools to large and small private houses, both in the country and in cities. The most suitable ones were established as auxiliary hospitals.

Auxiliary hospitals were attached to central military hospitals, which looked after patients who remained under military control. In all, there were over 3,000 auxiliary hospitals administered by Red Cross county directors.

They were usually staffed by;

A Commandant, who was in charge of the hospital (except for medical and nursing services)

A Quartermaster, who was responsible for the receipt, custody and issue of articles in the provision store

A Matron, who directed the work of the nursing staff & members of the local voluntary aid detachment, who were trained in first aid and home nursing.

In many cases, women in the neighbourhood volunteered on a part-time basis, although they often needed to supplement voluntary work with paid labour, such as in the case of cooks. Medical attendance was provided locally and voluntarily, despite the extra strain that the medical profession was already under at that time.

The patients at these hospitals were generally less seriously wounded than at other hospitals and needed convalescence. The servicemen preferred the auxiliary hospitals to military hospitals because they were not so strict. Also, auxiliary hospitals were less crowded and the surroundings more homely.

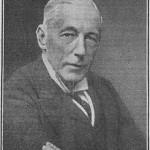

The commandant of the Rusholme Red Cross was a Physician from the Manchester Royal Infirmary, Dr Ernest Bosdin Leech. He was the third son of Sir Bosdin Thomas Leech, one of the most influential figures in Manchester's economic and political scene, who served as Lord Mayor in 1891-2 and was knighted for his work on behalf of the Manchester Ship Canal.

The commandant of the Rusholme Red Cross was a Physician from the Manchester Royal Infirmary, Dr Ernest Bosdin Leech. He was the third son of Sir Bosdin Thomas Leech, one of the most influential figures in Manchester's economic and political scene, who served as Lord Mayor in 1891-2 and was knighted for his work on behalf of the Manchester Ship Canal.

Dr Ernest Bosdin Leech, like his father, was a remarkable diarist noting down every event from day to day. An eminent physician and lecturer he assembled a large and significant medical library relating to the history of medicine in Manchester. As well as early childhood diaries he kept a journal of his trip to Europe in 1909 and a daily record of his experiences as a medical officer in the First World War. He was an enthusiastic local and family historian who kept numerous books and folders of closely written notes, as well as retaining cashbooks, accounts and cheque stubs relating to their house on Daisy Bank Road, Victoria Park.

I would like to thank the Librarian of Chethams, Michael Powell who helped me find this information about Thomas Bosdin Leech and giving permission to reproduce extracts from the diary below. There is an extensive collection of material about the Leech family at Chethams Library and you can view it online by following the link below.

Dr Ernest Bosdin Leech account of the early days of the Rusholme Red Cross at Neuberg,(later Newbury) is also accompanied by some photographs below.

‘For some years before the Great War Dr William Coates had, as Director, been organising the East Lancashire Branch of the British Red Cross Society. For a short period I, together with Dr Hart of Streford, acted as Deputy County Director and for a much longer period, several years, I had acted as Commandant of the Rusholme Division.

This Division obtained as Headquarters, No. 5 Park Crescent, Victoria Park, Dr Mellands former house, and, when this was required for other purposes, it rented Neuberg in Daisy Bank Road, also in the Park.

This house was in June 1914 fitted up as a hospital for practice and demonstration purposes, and, at the same time an Inspection of the Rusholme Division took place. Beds and other materials were borrowed from members and others for the occasion, with the promise that they could be commandeered again if, what then seemed quite unlikely, a war did break out. Owing to this rehearsal and to the preparations it was possible to fit up the hospital within a short period of the commencement of war, and this hospital, with its name changed to Newbury, became one of the very first Red Cross Hospitals in England. It functioned thus throughout the whole of the war’.

Close-up of the photograph below is Dr Bosdin Leech, back to camera.

Photograph below is presumably of domestic staff at the Hospital

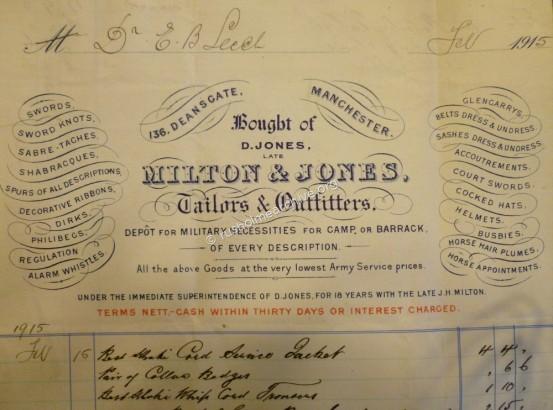

After the hospital was opened in Sept 1914 Dr Ernest Bosdin Leech left Neuberg and went to work at a large Red Cross hospital at Worsley, (pictured bottom rt below with the Worsley nursing staff) but left early in the beginning of 1915 having enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps.

His habit of meticulously preserving all of his bills & correspondence has proved to be a mine of information in considering the life-style of a middle-class Edwardian family. Below is the receipt for his wartime uniform from the Manchester tailors who kitted him out for service.

During the war in 1916 he married a widow, Mary Barker and in 1918 after the war was over he left the RAMC. With Mary they established a home in Daisy Bank Road just across the road from Newbury. He lived at ‘Chadlington’ in Victoria Park with his wife and two daughters until his death in 1950.He served both the medical community and particularly the Victoria Park Trust, writing a history of Victoria Park in 1937 when the Park Trust celebrated its 100th anniversary.

Amongst the first patients to arrive at Newbury in October 1914 were some Belgian soldiers who were conveyed to the hospital from the railway station by more volunteers, Mr George Gill and Mr Percy Smith.

They reported their journey to the local press in a letter saying,

“It was our privilege to convey the Belgian soldiers to their new temporary home at Neuberg in Victoria Park. Here they were received by Mrs Thorburn, (Vice-chairman of the Rusholme Red Cross) and a staff of nurses of whose kindness it is impossible to speak too highly. We would point out that all Red Cross work is honorary and that much of the expense of this hospital will have to be borne locally and we appeal to the residents of Rusholme for help in this worthy cause. We are informed that these new patients will need a diet in which fresh fruit and vegetables will play a prominent part as for the last two months they have subsisted on tinned meat-stuffs and Service biscuits.

Mrs Thorburn would therefore welcome gifts of fruit and vegetables, also tea, sugar and general groceries. We feel that the citizens of Manchester have only to be appealed to so as to respond most generously. Donations should be forwarded to Mrs Thorburn, Neuburg, Victoria Park”.

In the undated photograph below soldiers who were recovering from their injuries are seen in a fairly relaxed mood having been entertained by the Birch Lane Members Club, (Longsight), where bowls and tennis was popular - see the soldiers holding racquets and bowls on the front row, also the infant on the front row, right, wearing a soldiers hat!

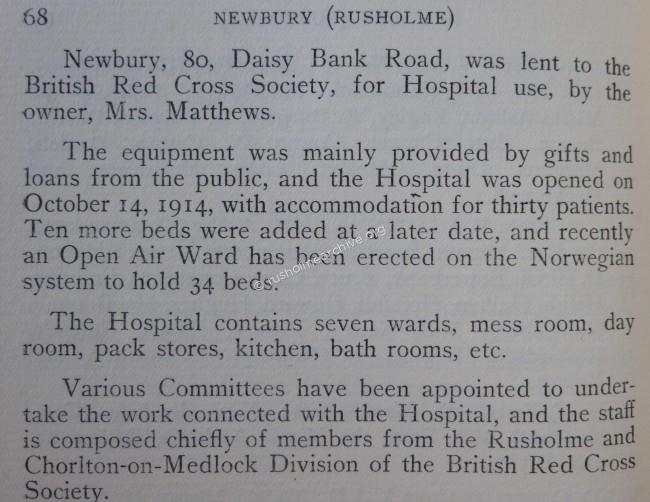

When the Red Cross first opened Newbury in 1914 30 beds were provided. The following year in 1915 a further 30 beds were provided, these were in the open air in the garden!

On June 15th the following report appeared in the Manchester Courier;

"To-morrow the Lord Mayor will open the open-air annexe in Daisy Bank-road, Victoria Park, carried on by the Rusholme and Chorlton-on-Medlock Division of the British Red Cross Society. This branch of the society’s work came into existence in March, 1911 but was then devoted more to educational purposes so far as the training of nurses in first aid and ambulance work were concerned. To-day the residence of the late Dr. Tom Smith has undergone a metamorphosis. Throughout, the house has been re-arranged in every department for the benefit of the wounded, 248 men having received treatment. The annexe provides accommodation for 30 more who will receive the benefits of the open-air treatment. Here is another instance of competent voluntary effort. The members of the local medical profession have volunteered their services, the nursing staff to a large extent are also volunteers, and to these have to be added organised committees of ladies and gentlemen, all working heart and soul for the welfare of those who are suffering for the cause of the Empire."

Below is a photograph of an 'Open-air Ward', but this one is not at Newbury.

The open air ward at Newbury was described as follows;

The open air ward at Newbury was described as follows;

The open-air ward is a wooden pavilion under the shade of the trees. One side of the pavilion is open and has only blinds, like shop blinds, to keep off the rain that will drip from the trees in wet weather. The ward is, indeed, an experiment, for which Professor Thorburn is responsible, in the open air treatment of the wounded, and it has been built to the designs of the Manchester Corporation architect, Mr Henry Price.

Professor Thorburn (Photo on the right), made a statement regarding the advantages of open-air treatment.

“In previous wars when the hospitals were overcrowded and they had to treat to wounded men in the open air, they were surprised to find that many whom they thought were dying recovered in a wonderful way. In certain diseases due to germs, such as consumption, treatment in the open air is infinitely the best method.

For the treatment of the infection of a wound the most valuable thing is what Charles Kingsley called "God's oxygen."' From shock to the nervous system, resulting from wounds or the awful strain of battle, the most valuable thing is the sight of the open country, not the sight of closed walls.”

I find it personally ironic that Sir William referred to the value of fresh air. He was, apparently a life-long chain smoker and died from lung cancer at the age of 62.

Professor William Thorburn was a leading surgeon at the Manchester Royal Infirmary and lived at Oxford Lodge Oxford Place Victoria Park with a family of 3 boys & 3 girls. They had a staff of four. The following biographical note is from Wikipeadia.

Sir William Thorburn K.B.E., C.B., C.M.G., F.R.C.S (7 April 1861 – 18 March 1923) was an English surgeon and pioneer in modern spinal surgery. At the time of his death he was Emeritus Professor of Clinical Surgery at the University of Manchester. In Manchester, Thorburn filled most of the positions of honour in scientific medicine, and he was appointed Deputy Lieutenant for the County of Lancaster. The outbreak of the First World War found him already holding the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the Royal Army Medical Corps, Territorial Force, and he was placed in command of the 2nd Western General Hospital. The war having taken from him his three sons, he was appointed consulting surgeon with the temporary rank of Colonel A.M.S., at Malta, Gallipoli, and Salonika, and in 1917 he filled a similar position in France. For his services he was awarded a C.B. in 1916, and a C.M.G. and a military K.B.E. in 1919, while during his stay at Malta he was given the honorary degree of M.D. by the University of Malta.

The photograph below was taken at Newbury and is marked November 1918 and so was presumably taken after November 11th when the war ended.

At the end of World War 1 Newbury was used briefly as a residence for American officers. Then it was purchased by Sir William Thorburn, he and Lady Thorburn living there until she died in June 1922. Sir William then sold Newbury to Harry Platt, (later Sir Harry & the third MRI Honorary Surgeon to live at Newbury). Sir William then moved to London, (perhaps to be nearer to his daughters ? – his three sons having predeceased him). He died in London in March 1923 and was buried in Manchester Southern Cemetery.

Sir Harry Platt remained in Newbury with his family until 1941, and then for a while the house was used by the army for administrative purposes. It was then acquired by Manchester City Council and used a home for elderly persons. More recently it has been used as a rehabilitation centre for patients recovering from alcohol dependency.

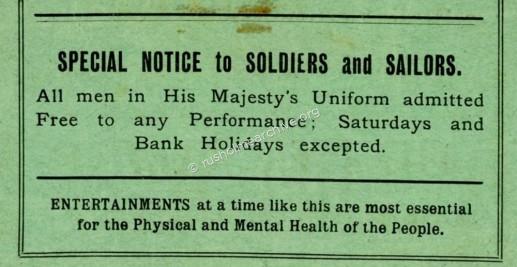

Patients at Newbury and all other military hospitals wore a particular uniform, 'hospital blue’ with a white shirt and red tie. The men in this distinctive uniform were a well-known sight in Rusholme, where the various places of entertainment, i.e. Leslies Pavilion, the Trocadero cinema generally offered them free seats. In the postcard below, undated but from the WW1 there is an interesting poem on the reverse which is also displayed below.

Another similar postcard below!

The notice below is from a programme for the Trocadero cinema, dated 1915.

Notice below dated 1915

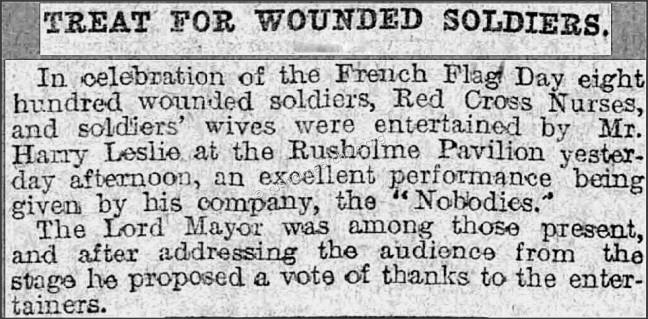

Harry Leslies Rusholme Pavilion funded beds.

The photograph below is at present an unknown location, the back of the card refers to a Rusholme Military hospital; the only bed that I know of that was named after Harry Leslie refers to one bed at Willow Bank Hospital on Moss Lane East. The photograph below, (when the note on the bed is seen in close-up) refers to five beds supported by patrons of the Rusholme Pavilion, whilst the other bed refers to the ‘Ladies Committee’ of Rusholme Pavilion supporting this particular bed. The interior of this building certainly does not look like any of the schools used in Rusholme as hospitals; Is it a picture arranged in the Rusholme Pavilion perhaps? Most surprisingly Harry Leslie does not seem to be in the photograph. (See the page above about Harry Leslies Rusholme Pavilion).

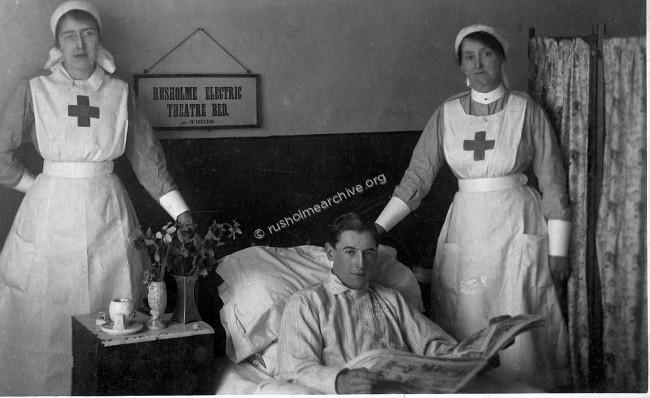

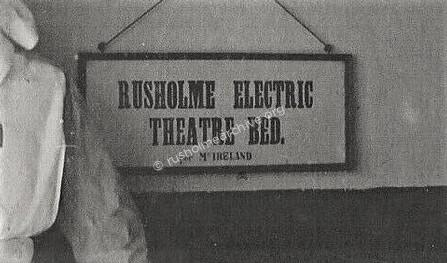

Rusholme Electric Theatre Bed.

* The Rusholme Electric Theatre patrons also supported a hospital bed as you can see in the photograph below.* Undated and and as yet I have not found which hospital had the bed.

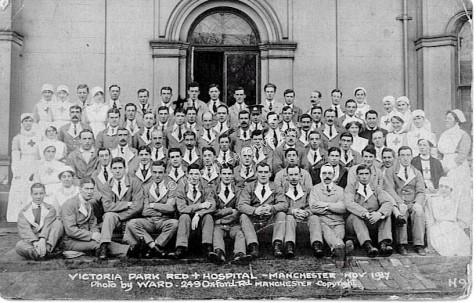

The photographs below were taken by a photographer, E Ward of 249 Oxford Road, Manchester, some are marked on the back with a pencil, ‘Rusholme Military Hospital’, others are marked ‘sample’. I acquired them as a set so presume they were taken in the wards at one or more of the locations referred to above.

(Since I first wrote about the photographs below I have come across some information that positively identifies the photographs of the Christmas tree being decorated as being the Heald Place school. The date is probably 1915.)

Of all of the photographs in this collection I find this one above the most poignant and moving – were these young men, smiling for the camera, and recovering from their wounds to be sent back to the front-line? Perhaps they were to be amongst the millions yet to die in action?

More photographs of ward interiors below.

Photograph below is dated 1914 from Birch Studio, Dickenson Road. Perhaps a local resident newly enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps?

The card below is an example of an embroidered greetings card - they were very popular during WW1.

A Personal Memory

Norah Horrocks was born in 1904 and had lived all her life in Rusholme. As a young girl during World War I, she recalls a wartime childhood.

Norah Horrocks was born in 1904 and had lived all her life in Rusholme. As a young girl during World War I, she recalls a wartime childhood.

"I used to queue for food. I'd come running out of school and say to Mother; "There's a queue outside the Maypole [at the corner of the Walmer Street continuation] - they're selling half a pound of butter." Oh it was great having half a pound of butter, great. I had lots of experiences like that during the war. The Belgian Chocolate Shop on Wilmslow Road made beautiful chocolates. You could get a quarter when they had a queue. That was a great treat that was.

Casualties of War

There were ladies on the trams at the time and people weren't allowed to run motor cars, as the petrol was rationed, but there were always lots of ambulances on Wilmslow Road. We had a shop called Minshull's Sweet Shop in Walmer Street, and they sold all sorts of things. Well, there was a boy there my age, we were very friendly. I cried for three nights every night for he got killed on Wilmslow Road, crossing the road, knocked down by an ambulance.

At the time there were hospitals for soldiers all over the area. And the ambulances, you see, they came flying down the road, taking them to Grangethorpe, taking them to Ellesmere House, Newbury, Moseley Road School, and there was Heald Place School.

That was built for a school, but never opened as a school till after the war, because that's where I went. And we went instead to a tabernacle place, because the school building was turned into a military hospital. It was lovely inside, very suitable.

Then there was Grangethorpe which is now the High School - that's where you'd see the wounded soldiers sitting on the seats around. They wore a blue uniform then. I'd be given cigs to give to the soldiers sitting in Platt Fields.

My brother was a prisoner of war, taken on 21st June 1918. We eventually received a buff card saying 'Safe and Sound'. He escaped with two others, and they were taken in by a Belgian farmer. His first cup of tea - served in an empty salmon tin - he always said was the best cup of tea he'd ever had. But when he came back from the prison camp he told us, "I've never seen human beings treated like that, and I never want to talk about it." And he never did.

Playing in Platt Fields

I used to play in Platt Fields with all the boys and a bat and a ball, or else go what we call travelling. It's a silly thing to say, but there's a brook there - it's all railed off now, but it wasn't then. When I was a child we used to go, run backwards and forwards right through the tunnel into Birchfields. That was my summer holiday excitement. Mother would have gone mad if she'd known.

The Suffragettes

Some suffragettes lived in the road I lived in, Oxney Road, and there was a suffragette lived next door to us, Mrs. Ratcliffe. And they used to come up in the middle of the night, depositing these suffragettes into this lady's house next door. Mother had a very great respect for the work of the suffragettes - they were fighting for women's rights, you know. There was a hall in Old Hall Lane - the Exhibition Hall. Well, they set it on fire. And my mother remembered my brother and sister [my brother was 12 years older, my sister 5 years older] went to watch the fire. Great excitement. The hall was burned to the ground.

After the War

When the War ended there was so much elation. I was 15 years of age about, and I can remember standing at the corner of Wilmslow Street and Walmer Street, and the people shouting "The War is Over!"

As far as jobs were concerned when the came out of the war, there was very little work for men. And I can always remember this experience - I've never forgotten this. There was a picture house called The Oxford Street Picture House, a very popular one, and my brother told they wanted a commissionaire. By 8 o'clock in the morning there was a long queue. Work was terribly hard to get, terribly hard.

Another War Looms

I thought it was dreadful, absolutely dreadful. They had a walk for the peace movement. I once followed the peace movement, because I thought it was terrible, talk of war again.

And a friend of mine said to me - she was very academic, she was an MA, years older than me, a very wise woman - she said, "Are you coming with me? I am joining this meeting." It was held at a picture house. So I joined her.

And the Peace Pledge Union, held at the Friends Meeting House -1 remember going to one or two meetings, in fact I went to quite a few during my lunch hour, because they held them for the benefit of business people. And they used to last about half an hour.

I thought it was terrible. It was a very common belief - to think they were having to fight again. So there was quite a bit of peace activity."

The WW1 memory of the late Norah Horrocks was published in 1992. It was part of the Rusholme Project started at the Birch Community centre with the intention of collecting memories of local residents. Published under the title of MEMORIES: Reminiscences of Rusholme by ID Books. I would like to thank Clive Hopwood, the Editor for being given permission to reproduce Norah's memory here on rusholmearchive.org. Copyright law requires permission to be given by the author but unfortunately this has not been possible. If any relative of Norah Horrocks has cause to be aggrieved by the publication of her memory please contact me; admin@rusholmearchive.org.